‘Monsters: The Lyle & Erik Menendez Story’ TV Review: Exquisite Storytelling Marred By Lax Editing

2.5/5

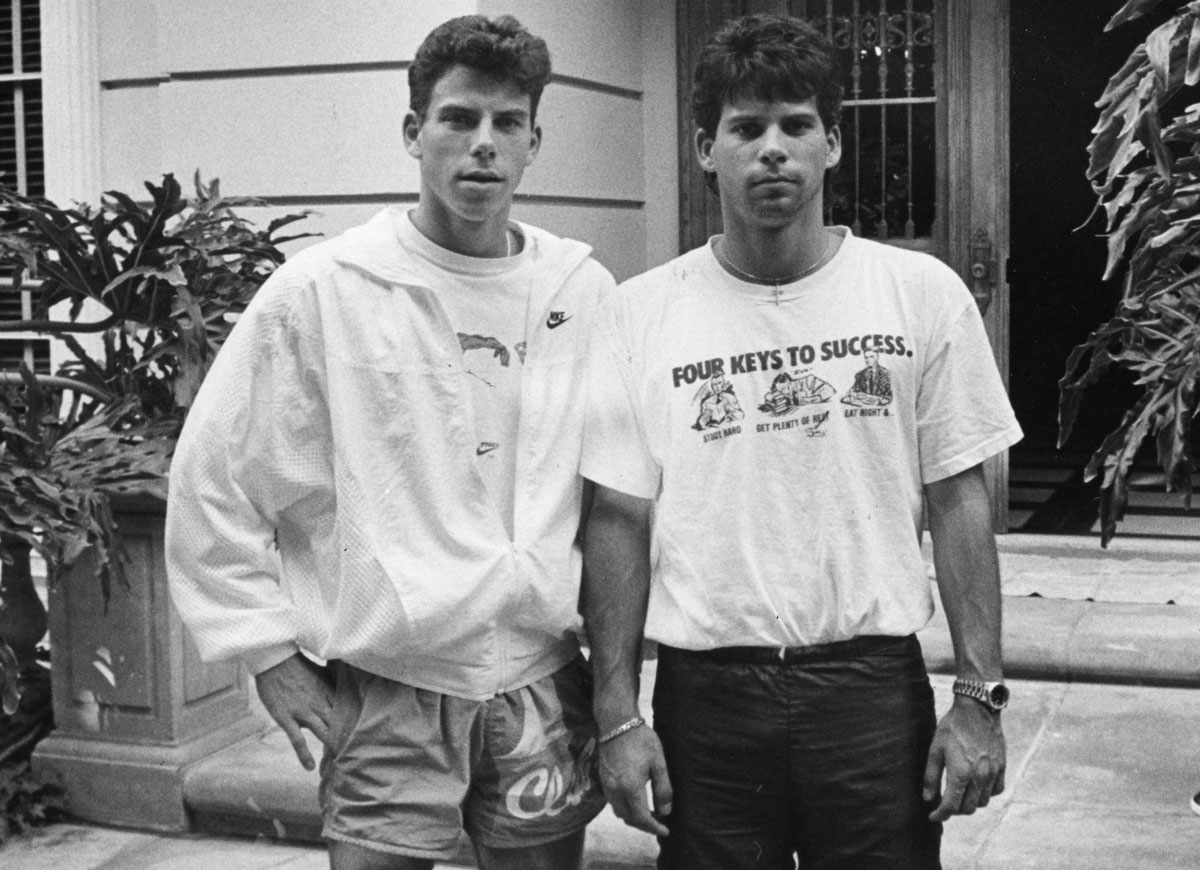

This installment of Ryan Murphy’s Monsters dramatizes the 1989 murder of José and Kitty Menendez.

Lyle and Erik Menendez were convicted of their parents’ murders in 1996. The brothers, currently serving lifetime imprisonment without possibility of parole, maintain their claim presented in court that they killed José and Kitty out of self-defense after years of physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

Over nine episodes, Lyle, played by Nicholas Chavez, and Erik, played by Cooper Koch, are portrayed through constantly shifting lenses and theories concerning the murders; the audience is volleyed back and forth between compassion and doubt. The show wants us to ask questions: Are the boys victims of abuse? Are they sociopaths? Did they kill out of self-defense? For money? To protect darker family secrets? The show has sparked particular controversy for implicating an incestuous relationship between the brothers.

From a craft perspective, aspects of this series are very successful. The acting is exquisite; Chavez and Koch elegantly convey the nuanced trauma and psychology essential to the story. The script also has its gorgeous moments. I would direct interested viewers to Episode 5 with trigger warnings for graphic descriptions of abuse. The incredibly potent 35-minute episode is a single continuous shot of Erik detailing his horrific homelife to his defense attorney, Leslie Abramson (played by Ari Graynor). The writing and performance are deeply disturbing and brilliantly executed.

Beyond some truly notable acting and production, the show drags far beyond the point of doing the complex story justice. I can only ask, “Who’s the real monster?” so many times before wondering if it might be the editors.

Murphy explained that the series aimed to lay out all the facts and allow the viewer to make up their own mind about the innocence, guilt and morality of the parties involved, a tall order for a Netflix crime drama. Sitting through approximately seven hours of back-and-forth between harrowing recounts of abuse and slices of evidence against the Menendezes’ claims, I found myself less concerned about exploring the motives for a decades-old murder and more troubled by the creators’ motives for filling nine episodes with the same questions about the legitimacy of the brothers’ trauma.

Murphy has stated the show’s partial intention of respectfully introducing a conversation about male sexual abuse into the mainstream. There is certainly an argument to be made that media like this draws attention to issues such as this, especially since attitudes towards sexual abuse have (hopefully) shifted since the 90s.

However, given the unknowns and particulars of the case, one wonders if a sensationalist medium is and will ever be appropriate for recounting it. In the season finale, as the jury debates whether to sentence Lyle and Erik to death, a jury member says, “if there’s even the slightest chance that what they said is true, I’ll tell you right now, I’m not gonna be the one responsible for taking their lives.” Arguably, the possibility of intense physical and emotional abuse also makes simultaneously confirming and denying those allegations in a mainstream dramatization morally challenging.

The series has prompted conversations about the true crime genre as an exploitation of victims. Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story was met with similar controversy upon its release in 2022.

There’s a lot about this show that worked and a lot that didn’t. Viewers interested in the Menendez case might find this series compelling. However, particularly considering how much space has opened up for discussion of sexual abuse in the last few decades, I wouldn’t consider it a one-stop shop for understanding a real story of brutal murder.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment