Is Horror Dead?

There is an unnamed feeling sharing a constellation with curiosity and fatalism that makes us seek out fear and makes the horror genre successful. We want to see others endangered and killed so we can look death in the eye from an insulated perch — the characters could be our proxy and we can somehow make death and evil a little less scary, or a little less real, because in some way we’ve already faced it, or faced something worse.

Recycling Horror: Found Footage And Remakes

Like every genre, horror suffers from too many sequels and remakes, though that isn’t the only problem. Horror movies just don’t pack the wallop they used to, at least not as often. The problem with horror films these days is a combination of three things: oversaturation, franchising and a lack of originality.

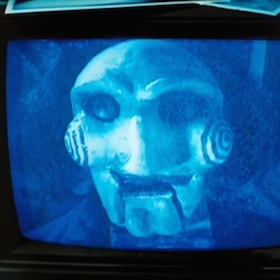

Horror is now a business run with the idea of creating franchises on the cheap — like Hostel (2005), Saw (2004), or Paranormal Activity (2007) — and churning them out until the audience chokes on it because of all of the derivative rip-offs and creative bankruptcy. Once that happens, new gimmicks are devised to start the whole cycle over again. If creating is too much work, just reboot something with an established name and hope for the best — A Nightmare on Elm Street (2010) and Texas Chainsaw 3D (2013) have both been released in the last few years and received little more than pity.

Attempts to reinvigorate the genre are more about regurgitating franchises or gimmicks from the past. Torture porn wants to harken back to the days of borderline snuff with Cannibal Holocaust (1980) or I Spit on Your Grave (1978), both of which suffered recent remakes, while found footage films like Diary of the Dead (2007), the Paranormal Activity franchise, the first part of Hellraiser: Revelations (2011) and countless others attempt to recapture the massive success of 1999’s The Blair Witch Project (or at least use it as a cover for their terrible production values).

When rip-offs aren’t in production, sequels and remakes are made to cash in on established properties. One of the problems with the Saw and Paranormal Activity franchises was the fact that they were being produced on a yearly schedule, leaving very little time for story and script revision; without the refinement, the products were often padded for time or outright sloppy, full of unfinished subplots and widening plot holes.

In general, found footage horror films are a melting pot of horror and business. They are scary in a manipulative way, as their grainy and unsteady view creates a faux-realism. The technique uses the fundamental fear of the unknown and of the dark, but, in truth, is an excuse for creating something on the cheap, and in its either ham-fisted exposition or lack of explanation, only remind the audience that what they’re watching is a movie — a barely visible, often incomprehensible movie at that.

The Difference Between Fear And Disgust

The question horror writers and directors stopped asking was Why? What’s the point? The problem with torture porn is that it’s torture porn, not horror. You’re not scared — just disgusted or disturbed. Both these feelings share some commonality with terror, and can confuse some into believe that what they are feeling is fear. If asked, ‘What’s the scariest moment in the Saw series?’ your mind will travel to a moment of violent gore, but that’s not fear. That’s a reaction to violence. Were you at all terrified during Human Centipede (2009) and A Serbian Film (2010) or was that nausea? These films exist as a shortcut to horror, a highlight reel of all the icky parts without those bothersome, albatrosses-like plot, reason or character.

In order to find good horror, you have to go somewhat underground and away from Hollywood. Farther than the surprisingly capable Insidious (2010), but not so far that you end up at I’m Not Jesus, Mommy (2010). On the way you’ll drift towards the enjoyable Would You Rather (2012) and the exciting You’re Next (2011) before settling on the big prize: The Descent (2005) a darkly lit truly scary work that relies on extreme emotional frailty, physical exhaustion, redolent paranoia and escalating claustrophobia. The brutality and the cave thematically link to the story and the character arcs are thought out and successful. Furthermore, The Descent has a satisfying and ultimately surprising ending that underlines the high emotions, and suggests that the characters of Sarah (Shauna Macdonald) and Juno (Natalie Mendoza) might be worse than the atavistic troglofauna Fluke Men that have pursued them.

What’s especially interesting is the work done to establish circumstance and character. Each character is given at least some measure of development and each actor is given a moment to shine, though the focus is Sarah and Juno. Writer/director Neil Marshall created something really spectacular by understanding that a writer’s best friend — especially with such a small budget — is character development and mood. The fact that we’re given reason to like the characters — even the technically villainous Juno is three dimensional and complex — makes us worry for them, rather than wait impatiently for ‘Whatever her name is’ to die next.

Dig deeper, you’ll come to Antiviral (2012), written and directed by Brandon Cronenberg, son of the legendary David Cronenberg. It concerns Syd March (Caleb Landry Jones) who works for a company that purchases viruses and illnesses from celebrities and sells them to their fans. The film satirizes the cult of celebrity and is hypnotic, horrifying, nightmarish and compelling. It is theme and setting over all else which makes the film and its characters sterile, though that may be the point.

Texas Chainsaw 3D: An Analysis

Now, let’s compare that to Texas Chainsaw 3D, a major studio feature that — of course — carries the name of a well-known series, and released in theaters around the world. Admittedly, the germ of the idea isn’t terrible; in actuality it’s audacious. It picks up directly from the end of the original; the Sawyer family is essentially wiped out by the sheriff’s department after the allegations made by Sally, who escaped. This is the last good idea the movie presents. From there we go down the length of tropes and genre clichés: tripping while running, bizarre twists, poor decision making, cheesy one-liners, cheating spouses and true untethered stupidity. Trey Songz is in the film, apparently allergic to any fabric, in the hopes that his fans would show (they did; it was one of the worst movie going experiences of my life) and bump up the numbers. Songz had no acting talent, nor did his costars (though Alexandra Daddario really came into her own in True Detective).

It’s truly difficult to measure the sheer stupidity and laziness of the script written by Stephen Susco, Adam Marcus, Debra Sullivan, Kirsten Elms and directed by John Luessenhop. Arguably the worst aspect of the film is its entire design. The original film takes place the year it was filmed — 1974, and 3D establishes that it’s 18 years later when Heather (Daddario) returns, meaning the action takes place in 1992. However, it takes place in the present. Modern clothes, modern tattoos, music, references and many, many smart phones. This inconsistency is, of course, never addressed and somehow the studio and the screenwriters managed to miss this — or, in the more likely case, didn’t care.

Like any 3D film, the actual 3D did nothing for the movie. It served as a way to drive ticket sales up and hopefully turn a profit. The film did, but just barely. There’s a saying about the banality of evil, and Texas Chainsaw 3D encapsulates the concept so well that to measure the sheer nature of its awfulness is like attempting to count the stars in the universe. Worse, it almost makes The Purge look Oscar worthy. It is, essentially, a disease placed on film.

When you have something with as many subgenres as horror does, it’s impossible to say there is a solid blueprint to what is right. The problem is the lack of interest in a new voice. And, without a certain level of time, money and talent, it’s rare for a horror movie to actually turn out well. If it is given mainstream release from a well-established studio, it will likely be watered down and continue to hammily embody the tropes associated to the genre so it can appeal to a wider audience.

Horror is now more a parody of itself, self-effacingly playing to its audience in a pandering fashion. Bad guys don’t get scarier with each film, they simply become boring. Franchises are formed not so much out of story necessity but because of its box office potential. If something works do it again and makes a dozen more rip-offs in various genres about it. Rather than allowing something to be special, it’s run into the ground until the box office is empty.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment