Howl

4/5

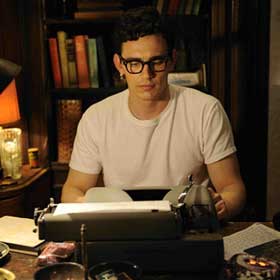

Directors/writers Rob Epstein and Jeffery Friedman (best known for 1995’s The Celluloid Closet) have paired together again to bring us Howl, a docudrama about the emergence of Allen Ginsberg’s poem by the same name on the 1950s American literary scene. The film is more of a celebration of Ginsberg and his poem than it is a story with a plot. It unfolds in three interchanging, parallel segments. The first features James Franco as Ginsberg performing a reading of the entire four-part poem to a rapt crowd at the Six Gallery in 1955 San Francisco. In order to liven up the reading of the poem, these scenes cut to animations that visually illustrate “Howl” as Franco recites, bringing it to life in a new way and emphasizing how entwined the poem is with the urban lifestyle. The second part shows Franco with an unseen interviewer, discussing details of his life and writing. Lastly, the film concentrates on the trial that surrounded the alleged “obscenity” of “Howl”—a trial that would play a pivotal role in the future of censorship by determining whether or not the poem should be banned.

Franco’s portrayal of Ginsberg, while noteworthy, is far from seamless. One almost can’t blame him because it’s a tall order to step into such iconic shoes, and I actually can’t think of anyone who might have done a better job. But, far from being a conduit to Ginsberg, Franco is clearly just an imitator. You can tell he’s acting. He overemphasizes Ginsberg’s excessive gesticulations and makes his voice a little too gravelly. Still, he is convincing, and his poetic training has paid off—his reading of “Howl” is extremely compelling and falls just short of Ginsberg’s own. Franco brings his own flare and informed interpretation to the lines. The graphics that take over a large portion of the film are interesting in their own right, but take away from the real attraction of Franco plainly giving a poetry reading. If Epstein and Friedman thought the viewers would need something more to engage them during the reading of “Howl,” they should have thought of their intended audience. These people will most likely already be poetry fans. Of course, the animations do succeed in shedding new light on the poem, but they give too much away by forcing their own interpretation onto the viewer. Furthermore, I’m not sure if they add enough to justify detracting from Franco’s engrossing reading.

The most interesting part of Howl lies in Ginsberg’s explanation (taken from real interviews) of how the poem germinated in his mind before coming to be the flagship piece of a poetic movement. In the beginning of the movie, he explains how he wrote the poem with complete freedom because he never intended to publish it. He wrote it merely for himself, because he worried about what his father would think if he ever got his hands on it. He frankly admits, “I didn’t want my daddy to read it.” This statement is both ironic and prophetic, because it’s the same sentiment that puts the poem on trial in the first place.

The entire movie is about this idea, which the very author of the piece shares. The movie’s portrayal of the trial, in which publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti (played by Andrew Rogers, who just sits beside his lawyer and, notably, never says a word throughout the film) of City Lights Books was brought up on charges for publishing obscene material, is also taken verbatim from real transcripts of what transpired. Both sides interviewed expert witnesses who attempted to delineate the qualities that give a work literary merit. The semantics and opinions of these “experts” all blur together until it becomes clear that such a thing cannot be determined and is, in fact, irrelevant to the issue of censorship. The trial footage is delightful and humorous on the surface because so much of it seems absurd to us today. However, it is also deeply alarming to acknowledge that such censorship issues were openly debated so recently, and that this urge toward intolerance is still part of our cultural climate. This part of the film really gives you something to think about and discuss with your friends afterward.

The movie also explores Ginsberg’s friendships with Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady (Todd Rotondi and Jon Prescott, respectively), plus his eventual relationship with Peter Orlovsky (Aaron Tveit). It portrays Ginsberg as a deeply intelligent and sensitive person who expressed himself through his writing when he felt personally stifled, which happened frequently since he often became enamored of straight men, or men who embraced a heterosexual lifestyle because society wouldn’t tolerate a homosexual one. Even when a series of mishaps lands Ginsberg in a New York City mental facility, he is only spared shock therapy when he promises the doctor he will renounce his homosexuality. It is here he befriends Carl Solomon (pictured only in archival footage), for whom he writes “Howl” in the first place, to give him and those like him a voice.

Epstein and Friedman definitely think of Ginsberg as someone who wasn’t aware of his own bravery. He even denies the existence of a “beat generation,” and, by association, his own elevated placement in it, stating modestly, “There’s no beat generation. Just a bunch of guys trying to get published.”

Howl is not for everyone, but if you are a fan of Ginsberg and his work, or even Franco and his, this is the movie to see. It takes a thoughtful, measured, and reasoned look at Ginsberg’s early life, relationships, and writing. Though its tendency to extol the poet might be a bit excessive, at least it offers this interpretation based foremost on facts. Some of the imagery is a little too showy or obvious, like when the camera follows Ginsberg walking along the cracks in the sidewalk, but these moments are few and far between. The supporting roles are all small, solid, and understated. No one is trying to be the “star” of this movie, which is extremely gratifying. Even Franco manages to step back enough in his (sometimes anxious) portrayal of Ginsberg to allow the main character of this film to really be the poem itself.

Starring: James Franco, David Strathairn, Jon Hamm, Bob Balabam, Alessandro Nivola, Treat Williams, Mary-Louise Parker, Jeff Daniels

Directors: Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman

Runtime: 90 minutes

Distributor: Oscilloscope Pictures

Rating: Not Rated

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment