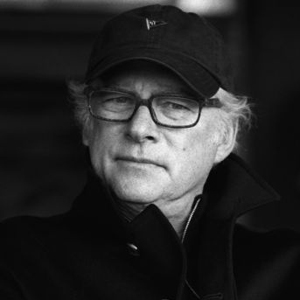

Barry Levinson On 'The Bay,' Shooting With An iPhone

Legendary director Barry Levinson is known for his bold approach to tackling serious subjects. In his latest project, The Bay, he finds a fresh and very modern form for his spine-tingling faux-documentary, which is partly based on the very real environmental emergency in the Chesapeake Bay. "The facts kind of rattled around in my head, and then it sort of lead to a scenario of The Bay," Levinson told Uinterview exclusively. "And I thought, 'Gee, I take this fictitious story and bring 85% of this factual information into it, kind of infuse it, make it interesting, scary.' And that's how it evolved."

Levinson, 70, who was raised in Baltimore, first worked as a screenwriter for Mel Brooks' comedies in the 70s and then moved on to directing in the 80s. Focusing many of his films around the Baltimore area, he found hits with Diner and Tin Men, as well as a sports fan favorite, The Natural with Robert Redford. He is perhaps best known for his work with 1988's critically and commercially successful Rain Man, which stars Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman and garnered four Academy Awards including Best Picture and a Best Director nod for Levinson.

In The Bay, shot using more than 20 different types of cameras, including iPhones, Skype, Apple Photobooth and squad car cams, Levinson sets out to tell the tale of the Chesapeake Bay, which suffers from 40% marine dead zones due to toxic pollution. The director found the perfect villain in the form of the isopod, a real marine creature that enters the gills of fish and then eats out its victims' tongues and replaces them with their own bodies.

| Get Uinterview's FREE iPhone App To Record Celebrity Video Questions + Get Daily News Updates here!

| Get Uinterview's FREE iPad App and watch our videos anywhere!

I was approached about doing a documentary about the Chesapeake Bay because it's 40% dead and all these issues around that. And I got the facts together, pretty scary facts and I thought, 'Well you know, I don't know that I can do a better job than Frontline, who did a very good documentary about it. I don't know if I can improve upon that.' The facts kind of rattled around in my head, and then it sort of lead to a scenario of The Bay, and I thought, 'Gee, I take this fictitious story and bring 85% of this factual information into it, kind of infuse it, make it interesting, scary.' And that's how it evolved.

No, I didn't have a desire. It wouldn't even have occurred to me. It's only just literally the progression of events. Here's an idea. I want to tell it in this story form, therefore, this will happen. And this will happen, then this will happen. It's just that.

Well, I'm not that interested in that. I mean I didn't even think of the movie as this 'found footage' thing, because that's somebody with a camera, and they're running around or whatever. That seems so far removed from what I was thinking about. You define it however you want to define it. I was thinking about if something happened in the town, and there was a catastrophe today. If we gathered and there was no media, how would we know what happened? This is the first generation that's got cell phones, e-mails. It's texting, it's Skyping, it's doing every kind of social media thing imaginable. Well, that'll give you a picture unlike any in the history of mankind. So I was thinking more like an archaeological dig. I wasn't thinking of Cloverfield because someone had a camera and was wandering around town. So I was looking at it from this archaeological, anthropological look, because it's got so many different people who are doing all of these things. It's this multiple — 10-12 stories playing out, so that's why I thought of it a different way.

It's fun, and it's exasperating because there's no video playback until afterwards. So you get someone like the iPhone girl, and she goes into a room, you tell the actor what to do. Now you gotta leave her in the room alone because otherwise you'll be seen, and she's video-ing and doing all this stuff, then afterwards you got to bring the iPhone out and you take a look and see what she did. Sometimes we give a camera to somebody and we go to take a look, and there's nothing there because they didn't hit the record button!

[laughs] So it's not quite the same, but that's the nature of the beast.

The isopods are in the Pacific and they have now migrated to the Atlantic Ocean, they have not come in to the Chesapeake which is one of the story points that we play out in the fictitious part of it. Isopods do go from being considered sea-lice to two-and-a-half feet long, and one of them tried to burrow its way into the side of a submarine. We mention that in the movie. So those creatures are real, they do go into the gills of a fish, they do eat the fish and then eat the tongue of the fish and then eat its way out, so they are for real. So they are this creature, this villain in the piece.

Well, it's a resonance because you're watching this, the largest estuary in the United States, and it's 40% dead because of negligence, it's not like we don't know how to fix it. Everybody knows how to improve it, but no one's had the will to step forward and to bring this to a head and begin to at least correct some of the ills of it all. It can be done. Everybody says, 'Well you know the economics, we don't want to lose jobs.' We all know about those things, but there's ways to improve without everybody going into the frantic mode of the economics of it all. There are ways to improve, because what's going to happen is if it tips too far the other way, the economics are going to be far worse than the economics right now. Because then it's going to kill off the recreation business, it'll kill off the hotels, it'll kill off the restaurants, those that live along the waters there, their values will drop. That side of the economics nobody is dealing with. Right now, it's the economics of the chicken farms, et cetera. But there are ways to improve these things without everybody going into panic mode and just systematically work to say we have to do better. We can do better.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment