In Treatment: Season 3

3.5/5

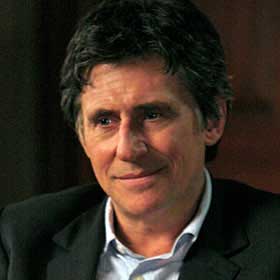

HBO’s half-hour drama In Treatment earns points for continued originality even as it escapes cancellation by the skin of its teeth. It has a unique premise and format that really hasn’t been seen on television before, which is perhaps why HBO keeps renewing it despite disappointing ratings. The program surrounds the professional and personal life of therapist Dr. Paul Weston (the charismatic Gabriel Byrne), a middle-aged recent divorcee with a couple of kids he barely sees, his own private practice and a stockpile of problems, including pretty transparent daddy issues and trouble drawing boundaries with his clients. Hence, In Treatment’s problem is not its lack of conflicts. The very originality of the show’s format may also constitute its struggle, as the pace is slow and conversational and it’s really “about” the subtle changes that occur through talk therapy, as well as the relatively complex idea that no one is “normal.” An American audience accustomed to fart jokes and exploding cars simply may not have the attention span for the unostentatious, solemn, thoughtful series that manages to delve into the common problems that affect the human psyche in a comparatively short time frame, which is actually about half the duration of a typical therapy session.

The show is modeled on the concept of the case study. Each half-hour episode is devoted to an in-house therapy session between the talented, intuitive but sometimes self-obsessed Dr. Weston and a different patient. The writing provides the most intimate glimpses into these characters’ histories and neuroses, hence, all the juicy stuff is there (relationship issues, depression, megalomania) and the writing remarkably achieves meaning and insight, but never overextends itself. Perhaps this is due to the show’s cozy, manageable scope. Or maybe the writers just have an unusually solid and intuitive grasp on the human condition.

Each of the four weekly episodes (two on Monday nights; two on Tuesday nights) follows one patient at the same time each week, just like real therapy sessions. Dr. Weston’s sessions with Sunil (Irrfan Khan), a grieving widower from Calcutta whose son and daughter-in-law have uprooted him from his home to look after him in New York, air Monday nights at 9 p.m., followed every week at 9:30 p.m. by his sessions with Frances (Deborah Winger), an aging actress whose life of self-absorption is leading her toward some kind of psychic break. Tuesday nights kick off at 9 p.m. with Weston and Jesse (Dane DeHaan), a defensive gay teenager struggling with issues of sexuality and identity and the last of the four “therapy session” episodes is perhaps the most revealing, as it features Weston as the patient, “in treatment” with his new psychotherapist, played by Amy Ryan, who has a lot to live up to after the departure of Weston’s previous shrink, the deliciously condescending Gina Toll, played by Dianne Wiest. Still, these episodes are the real icing on the cake, revealing a lot of the hypocrisy and human weakness you find among people, regardless of profession. In other words, no one is above being screwed up, so if you’re expecting your therapist to be some kind of emotional guru, think again. Odds are he’s out there behaving in ways that make you look like the world’s most well-adjusted sucker.

Not that Dr. Weston is some kind of crazed lunatic. But he’s also no guru. He’s just struggling like the rest of us and Byrne plays his inner turmoil with expert precision and understatement. The series also tries to remove the mystery/stigma that surrounds traditional talk therapy by portraying it in a more realistic light – not as a catchall solution, but a simple conversation that two people have alone in a room. “Treatment” is also a metaphor for life, because every aspect of a patient’s life is magnified within this microcosm, and we are all — patients and therapists

alike – “in” some stage of trying to make sense of it. For better or worse, In Treatment doesn’t eschew the clichés surrounding therapy, either, because they are also part of the experience. Dr. Weston asks the “tough questions” that sometimes send his patients on tirades, experiences a staggering number of insightful comments, and often wonders how something makes someone “feel.”

In Treatment makes a pretty valiant effort of illuminating all this and the acting is certainly solid enough that you never ask yourself how solid the acting is. However, I can see why it’s failed to reach a larger audience. For many of the same reasons therapy itself carries a stigma, the show does as well. It’s too touchy-feely. Too righteous. Too exploratory. Let me put it this way—if you’re the kind of dude (or chick – in fairness to the subject matter I’ll refrain from certain presumptions) who went with bated breath to see Jackass 3D on its opening night, you’re only going to want to check out In Treatment when you’re ready for a nap. Otherwise, give it a fair shot, and reward HBO for keeping the faith.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment