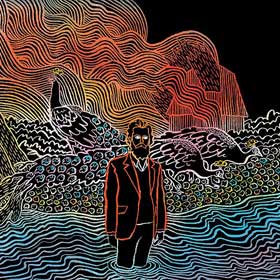

Kiss Each Other Clean by Iron & Wine

3/5

Iron & Wine—being the stage name of South Carolinian singer/songwriter Samuel Beam—burst onto the abstract scene known as "Indie rock bands with some degree of mainstream acknowledgement" during a crucial period in the gradual popularization of that genre. His breakthrough album, Our Endless Numbered Days, arrived just two years before the comparatively astronomical successes of Arcade Fire's Neon Bible, Modest Mouse's We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank and The Shins' Wincing the Night Away: the moment when indie, in a sense, "broke." The album peaked at #158 in the Billboard Charts, its success aided in no small part by the prominent use of an earlier song, "Such Great Heights", in the hit film Garden State, and appearances in the film In Good Company and the television series Six Feet Under, Life As We Know It and Grey's Anatomy, of the album's most popular song, "Naked as We Came," an autumnal, melancholy love song which, oddly enough, features backup vocals from his sister, Sarah Beam.

A few years ago, my father and I watched the concert documentary Heart of Gold on television. While I felt that Neil Young's performance of the title track was somewhat lacking in enthusiasm, my father contended that, although Neil Young was not "selling it," it was a decent performance. Until that moment I had never thought of an artist like Neil Young or, for that matter, an artist like Samuel Beam, who may be cited as his direct musical descendants, as "salesmen." It had always been my belief that the conceit of the singer/songwriter genre was one of confessional honesty. But then it occurred to me that Iron & Wine has released a sexy duet with his sister, so I can only assume that, far from being involved in any sort of incestuous paramour, the Beams are more or less "performers of songs." While a cursory listen to such classic albums as On the Beach and After the Gold Rush suggest neither a salesman pitching, nor an actor performing, the dreaded thing, affect, seems to crop up occasionally on Iron & Wine's latest release, Kiss Each Other Clean–his first for a major label, Warner Brothers; his previous label, Sub Pop, being only subsidized by a major.

With its, I guess, "bold" studio experiments and choral overdubs, the clunky, awkward side one, "Walking Far From Home" constitutes a considerable departure from the quaint, lispy, bedroom noodlings of his earlier, thriftier aesthetic. In this instance, though it is rarely if ever not the case, more money has allowed for more gadgets and more downtime which, for many artists, can be very destructive, often leading to well-intentioned cannibalism. Much like Elliott Smith, another clear influence, whose "little" voice was always vastly more effective than his shaky and awkward "big" voice, baritonal Beam strains a bit in the alien nether-reaches of low tenor notes, making for a slightly uncomfortable listening experience, one that perpetually threatens to collapse at any moment. The intermittent bursts of sampled drums and glitchy synth effects tend to distract from the song's overall inspirational tone, signifying, as they do, virtually nothing at all.

What makes this jumble of musical ideas and stylistic threads so "kind of cheap" sounding is that their essential arbitrariness is heightened by Kiss Each Other Clean's firm foundation in a single genre, which could be most reductively described as Post-Alternative Country Indie Folk. In a sense, Beam's sense of writing and arranging songs–his drum arrangements are a good example–is deeply rooted in a recognizable genre, so the introduction of "futuristic" junk feels more like litter than transmutation (see Wilco). While some might argue that something like "synth bass" has such a broad range of associations that it could even fit in to a modern day gospel-funk song like "Me and Lazarus," a slightly more semi-logical line suggests that synth basses have a narrower range of cultural ideas to which they are strongly linked in the popular imagination, a strong clue of which being that you probably didn't scratch your head when I referred to them as "futuristic"-sounding.

In keeping with the idea of Beam being an actor: while the affectations of "Walking Far From Home," "Me and Lazaurs" and the virtually uncategorizable messes that are "Monkeys Uptown" and "Rabbit Will Run" could be compared to an thoroughly unresearched Southern accent, "Tree By the River" could be considered a lazy performance in the role of a "stock character" — a sunshiny, circa 1970s AM Pop ditty, replete with a Motown-y bass line. In this case, Beam's research might have been a little too thorough: there isn't a single original note to be found in the entire song. For example, the name "Mary Ann" and the phrases "do you remember", "the tree by the river" and "when we were seventeen" all appear in various pop songs throughout history, by artists such as Jack Johnson, Earth Wind and Fire, Nik Kershaw, Pearl Jam and Leonard Cohen. Fortunately, Beam has gone through the trouble of singing all of them and in that order on the third track of his latest album.

One of the album's stronger songs, "Half Moon" finds the zealous performer reigning in his maximalist impulses for a tightly controlled, percussion-less country-rocker, featuring some excellent plucked or thumped guitar and tasteful bass rests, with only a few isolated bursts of zaniness. It seems that when denied the clutter of technological distractions, Beam is actually still capable of crafting nice little pop songs, even those with choruses and old time-y stuff like that. Similarly, the humble, just slightly too honeyed "Godless Brother In Lover" features some nice breathy falsetto singing that culminates in a dense vocal overdub strongly invoking Air Supply or something awesome like that.

"Big Burned Hand" is big and funky, punctuated by some strong saxophone playing, but Beam's (understandable) use of heavy vocal distortion render it a bit unlistenable. "Glad Man Singing" features a fairly decent approximation of Elton John's distinctive vocal cadence–even better than George Michael's–but is good for little else. Concluding the set is the fairly excellent "Your Fake Name Is Good Enough for Me," the only song on the album to successfully integrate the disparate elements floating throughout it, for its first three minutes, a successful synthesis of World Beat, Jazz and Prog vaguely invoking Steely Dan.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment