'Lincoln' Reigns Supreme

4.5/5

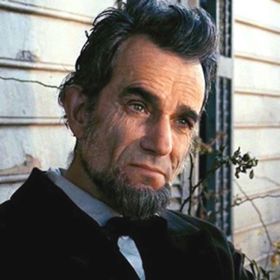

Lincoln, as directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Tony Kushner, goes beyond the biopic genre to create a political blockbuster in which the heated action unfolds in cabinet meetings, on the House floor, and on the streets of 19th-century Washington, D.C. The film, based on the book Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin, spans the final four months of Lincoln’s presidency as he fights tooth and nail to push the 13th Amendment through the House of Representatives. Daniel Day Lewis as Lincoln inhabits the lanky frame, the reedy voice, the languid walk, folksy wit, and political cunning of a larger than life American hero with a delicacy that humanizes him.

How does a pragmatic president with an ideal formed by the logic of justice pass a law that’s unpopular with a sizeable fraction of his legislature? Such is the question that Lincoln seeks to answer. Whatever concerns Lincoln may have had about questionable legality is superseded by his ardent belief that there should be equality for blacks under the law. Honest Abe bends law and truth for the greater good of man and to the benefit of the country. In order to pass the 13th Amendment, the film shows Lincoln appealing to his Secretary of State William Seward (David Straitharn) to procure the votes for the bill that they need — a task which involves hiring lobbyists to bribe representatives, and later the persuasive legwork of Lincoln himself.

A film centered on a single piece of legislation threatens to be dull — a cinematic C-SPAN. Yet, Kushner’s script elevates the language of ideas and allows smart political humor to give Lincoln the spirit it would otherwise lack. The trio of lobbyists played by James Spader, John Hawkes and Tim Blake Nelson, although at times a bit campy, ably mock the methods of getting things done in Washington. Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln and Tommy Lee Jones as Republican Thaddeus Stevens give memorable performances. Field, as Lincoln’s wife who has already suffered the loss of a son and fears her eldest (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) will join the Union army, descends into sympathetic hysterics — a talent of hers. (Steel Magnolias, anyone?) And Jones, for his part, is a sharp-tongued abolitionist who must replace his fiery demeanor with that of mitigated calm to do his part to pass the amendment.

In the foggy dawn of an April day of 1865, Lincoln rides on horseback through a body-strewn battlefield — his countenance gray like his hair and sallow face. Surrender is close at hand, the 13th Amendment has passed, and the struggle between liberality and selfishness has seen the former prevail in the tempering days of bloodshed. “Shall we end this bleeding?“ Lincoln asks, a note of pleading in his steady voice, of those on the council of the confederation. The dénouement of Lincoln sees Robert E. Lee raising the brim of his hat to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in a wordless surrender, Lincoln’s youngest son hearing of the death of his father from a theater stage, and lastly, Lincoln issuing the final speech of his presidency through the dim flame of a lamp to a crowd of both whites and blacks with his arms stretched wide.

All in all, Spielberg’s historical film succeeds in giving vigor to politics, and treats the role of a president in trying times with due gravitas. Without a doubt, there are parallels to be drawn between the political troubles of Lincoln’s time and those the country faces now. The system still yields sides with factions hard-pressed to reach compromises. Perhaps, while being a truly entertaining and engaging film about a great president of America’s history books, Lincoln also artfully exposes the flaws and the merits of our political discourse — giving both criticism and hope in equal measure.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment