'Cosmopolis' Drives To An Artistic Extreme

4/5

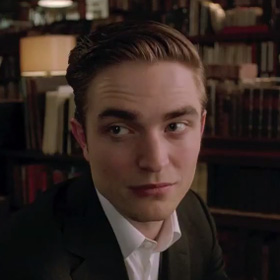

Director David Cronenberg opens his new film, Cosmopolis, with a quote: “A rat became the unit of currency.” The quote is by Zbigniew Herbert and also opens the novel by Don DeLillo on which the film is based. Cosmopolis follows Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), a curious and detached billionaire whose purpose in life is to predict the fluctuations of monetary gains. Packer lurches through the gridlock of Manhattan’s streets in an extravagant, insulated stretched limo: the president’s in town; there’s a funeral procession for a rapper somewhere in the nest of buildings up ahead; the city is at a standstill; his body guard stresses how these situations pose a security threat; still, Packer’s sole intention is to get his hair cut at a barber shop across town.

The dialogue is terse, nearly like an automaton. Mostly taken directly from DeLillo’s writings, it evokes a loose David Mamet-esque vibe, and perhaps even a less-twisted American Psycho. The basis of the film revolves around Packer, accompanied by his head bodyguard, Torval (played superbly by Kevin Durand). The majority of Packer’s time is spent in the back of his limo, seated in the glow of a large, high-tech chair where his advisors make one-on-one visits to discuss his quickly failing fortune. The truer identity of Packer is unveiled through these various “advisors," which include the likes of Jay Baruchel, Juliette Binoche and Samantha Morton, and who rendezvous in the limo to discuss strategies in regard to the Chinese currency, the Yuan. The issue is that Packer has bet against it. Now, the Yuan is slowly rising in market value causing his “tens of billions” of dollars in fortune to quickly evaporate. “A man rises in a word and falls in a syllable,” Packer states.

There is also Packer's new wife (Sarah Gadon) who he has yet to consummate the marriage with because she would rather conserve the energy for work — a bizarre excuse that speaks volumes of the world they live in, where value is placed on man-made concepts of satisfaction versus base and animalistic yearnings. Conversations are a flurry of tech-savvy jargon, philosophical in manner and just as equally murky on the reality, and practicality, of the words being spewed. Fittingly, the discussions revolve around that larger-than-life hypothetical concept of money.

For anyone with reserves about Pattinson leading the film, rest easy. His often rigid acting fits the part this time, and we’re even allowed glimpses into the true talent he possesses, notably in the later scenes featuring Paul Giamatti as Benno Levin, one of Packer’s former employees. Packer is a detached creature, observing the world as if through a microscope, attempting to find pattern and meaning in the organic fluctuations of a fallible human world. He has doctor appointments daily; today, he takes it in his limo. In one of the most (dryly) comic scenes of the film, his doctor performs a prostate exam and reveals matter-of-factly, as Packer carries on a sexually tense conversation regarding his financial assets, that Packer has an asymmetrical colon — a fact that bothers him immensely.

Interestingly enough, Cronenberg, who had some harsh opinions on Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises (also loosely based on Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities), claimed that superhero movies are merely for children — “adolescent in its core.” He told the Hollywood Reporter that “I don’t think they are making them an elevated art form. I don’t think [Christopher Nolan’s] Batman movies are half as interesting (as his film Memento), though they’re 20 million times the expense.” Intriguing insight from a director who’s most recent film deals with the same overlapping themes of class divides, unevenly distributed wealth, extravagance, and lack of inward contemplation. There is no denying the mass appeal of films such as the Batman trilogy, compared to any of its artistic counterparts (crowds didn’t flock to a midnight screening of Memento after all), but perhaps Cronenberg simply feels slighted that — despite his name and reputation — his choice to go out on an artistic limb is only opening to limited release while “a man in a cape” is making millions. Perhaps, his seemingly off-handed remark reveal his own frustrations with an industry that favors capital gain over artistic integrity, which seems fitting for Cosmopolis’ plot at least.

But in tune with Cronenberg’s legacy, Cosmopolis gorgeously peeks into the mental and physical deterioration of a 28-year-old billionaire and the world around him. With stunning filming, this collapse that Parker faces leads to a quiet and subtle examination, a pulling off of the veil. The limo serves as the physical and mental basis for Packer’s movement, hopping out occasionally to grab some diner food or a quickie in a nearby hotel, vandalized in a riot while Parker looks on indifferently from the still silence of the hull, driven all the way to the grungy limits of the city. It’s all very symbolic.

Before anyone can accurately (or more likely inaccurately) pigeon hole Cosmopolis, it might be advisable to view the film more than once. It’s clearly a necessity to pick apart lines — this did begin as a DeLillo novel after all — and to calculate all the facets at work before making an assessment. Attempting to weave its way through the demented psyche of capitalism, Cosmopolis is a peculiar meditation on the digital world that we are, rather than being thrust into, creating for ourselves; and on all the devastation mathematics and symmetry can cause on creatures that are anything but symmetric and easily calculable.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment