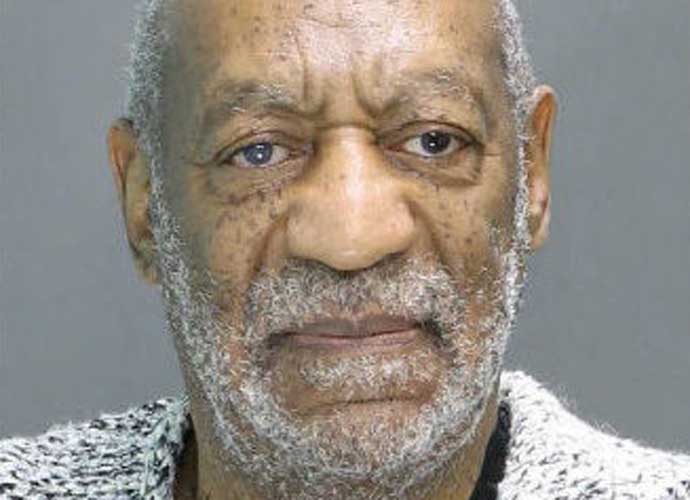

Bill Cosby’s Utter Fall From Grace: Why Just Him And Not Other Abusive Men In Entertainment?

As the Bill Cosby scandal continues to unfold, with the recent release of excerpts from a 2005 deposition of Cosby revealing that he admitted to procuring Quaaludes with the intent of offering them to women he wanted to have sex with, the push to tear down the once iconic and now infamous comedian has reached a fever pitch. More networks are pulling reruns of Cosby and The Cosby Show, a petition to the White House has been raised to revoke Cosby’s Presidential Medal of Freedom and even his staunchest defenders are turning against him. It seems Cosby’s legacy is sealed, not as the groundbreaking African-American comedian who introduced the concept of a black middle class family to mainstream white America nor as the fiery activist chastising poor black communities for failing to strive for personal betterment and embrace family values — a questionable legacy itself — but as a serial rapist whose every word, action and creative output will be forever tainted, even nullified, by the allegations made against him and by his own admissions.

There is no doubt that the dozens of allegations against Cosby are disturbing in the extreme, and if true — which, barring some vast conspiracy, it’s more than likely at least some of the allegations are true — then it is a travesty of justice that this man has not been held to account for his crimes and his hypocrisy on issues relating to his conceptions of how black families should live by his high moral standards should be exposed for the sick, cruel joke it is in light of these allegations. In fact, it was Cosby’s reputation as a “public moralist” that motivated the judge to unseal the 2005 deposition that has made it that much harder for any remaining celebrity defenders or fans to claim that Cosby is the target of a conspiracy or women who just want to cash in on settlement money.

And yet this case also raises the age old, seemingly impossible to answer question of whether one can separate art from the artist and judge it based on its own merits, regardless of the personality or crimes of its creator. With Cosby, it seems the public and entertainment industry has answered that question with a resounding “no.” It apparently doesn’t matter that The Cosby Show and his stand up acts were an indelible part of our cultural landscape for decades now that the monster behind the work has been revealed. And yet, in so many comparable situations in the past, the answer has been a contemplative “maybe” or an unashamed “yes.” Roman Polanski, the celebrated, Oscar-winning filmmaker, pleaded guilty to the statutory rape of a 13-year old girl in 1977, whom he sedated with champagne and Quaaludes, a heinous crime that caused him to flee the United States and never return in order to avoid facing a sentence. And yet, classics such as Chinatown and Rosemary’s Baby continue to be listed among the greatest films of all time, 2002’s The Pianist earned him an Academy Award for which he was conspicuously absent because of his legal problems related to the rape and entertainers and industry figures continue to star in and support his films.

There are plenty of other examples of creative men, both contemporary and historical, who committed or were alleged to have committed abusive acts against women or young girls, including Woody Allen, Sean Penn, Jimmy Page, Charles Dickens and Pablo Picasso, who are all still primarily defined by and admired for their work than they are denounced for their misdeeds and/or alleged crimes. What makes Bill Cosby so different? Is it the sheer volume of the accusations against him, showing that this was not an isolated incident, as in the case of Polanski? Is it indicative of the progressive, rising tide of feminism in our culture, wherein no man will be given carte blanche to subjugate women as was too often the case in the past? Is it his public moralist persona, that hypocrisy that motivated the judge to act? Is he a sacrificial lamb to atone for Hollywood’s past tacit acceptance and embrace of men who abuse women?

Or maybe it’s just because his artistic output and comedy just isn’t that amazing; certainly not amazing enough to overlook repeated allegations of rape. If I’m being perfectly honest, I’d be a lot more upset about Netflix taking Chinatown or Annie Hall off their streaming service than I am about reruns of The Cosby Show being taken off the air, not because I think Polanski or Allen are somehow untainted by the allegations against them whereas Cosby is tainted, but because those are two classic films that I love and want to have easy access to re-watch should the desire strike, whereas I’d probably never have the desire to watch an episode of The Cosby Show simply because there’s a million things I’d rather be watching. The Cosby Show has historical and cultural significance, for which I do think it would be a disservice to completely erase from history because of Cosby’s alleged crimes, but it’s not exactly the pinnacle of artistic achievement in the annals of cinema and television. So, I can’t speak for everyone else on the question of separating art from the artist, but for me, I guess the answer is simple, if somewhat unpleasant and unflattering for me to admit; if the art is good enough, at least in my humble opinion, I can overlook the transgressions of its creator in order to appraise and celebrate the work on its own merits, but if it doesn’t quite move me or enthrall me, and the creator happens to be an awful human being, I probably won’t care as much if their whole body of work collapses under the weight of that awfulness.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Click here for the 2015 CFDA Fashion Awards: Best Dressed Slideshow

Click here for the 2015 CFDA Fashion Awards: Best Dressed Slideshow

Leave a comment