The Skin I Live In

5/5

"It's important not to forget that films are made to entertain. That's the key," Pedro Almodovar said in 1999 interview, around the time of the release of his acclaimed masterpiece All About My Mother, which won him the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Three years later, Almodovar released what is still my favorite, Talk to Her, which nabbed him another Oscar for Best Original Screenplay – a category typically won by English-speaking, Best Picture contenders or quirky American indies. Since then, Almodovar has directed Bad Education, Volver and Broken Embraces, the latter two starring the endlessly watchable Penelope Cruz. Every one of these titles represents an extraordinary film; they unfold, wielding the weapons of narrative desire and genuine surprise, in a manner that nods to classic cinema but feels entirely new and modern.

The Skin I Live In continues this winning streak. Like all of Almodovar's films of this period (he's been making movies since long before 1999), it has provocative story elements, star power, cinematography and art direction that is almost criminally perfect. There is a feeling pervading theses films that Almodovar has complete control over everything – even the music seems plucked directly from the sinews of his own shrewd brain – and to me, this is a welcome feeling. Almodovar does not have to do much to earn my trust, nor that of many of his most ardent admirers. One need only sit back and enjoy, allowing oneself to be entertained, and Almodovar takes care of the rest.

When I watch a film by Almodovar everything makes a bizarre and twisted kind of sense. It's nearly frightening how intimate I feel with a film made – so it seems – with a viewer precisely like me in mind (not to mention a film rather cold toward the idea of intimacy). What am I like? In the tradition of B movie science fiction, I don't mind logical jumps or blatant departures from verisimilitude if there is a reward for leaving these accoutrements at the door.

In an Almodovar film, there is always a reward for taking something off, which often means baring your predispositions about sexual morality, or your inclination to balk at what appear to be purely attention-grabbing ploys. It's a kind of cinematic strip poker, played slightly backwards. Dispense with your unease about vaginoplasty, and you have a character who has undergone a nearly complete transformation into another character from an earlier act. Leave it to Almodovar to raise a woman from the dead by cutting off a man's penis! Accept that sometimes wayward sons show up at the door dressed in tiger costumes, and you get a villain who's also a savior who's also a figure for Almodovar's camp sensibility abruptly fast-forwarding the reel so we can move on with the rest of the action.

You can always tell an Almodovar film by the way it ends. Rather than a denouement that ties a bow around a neat package, we have the revelation that Almodovar has tricked us into watching a feature-length preamble to an entirely other and equally bizarre story – and like a poet he leaves us (thank God!) to imagine that story, rather than participate in the fetishization of sequels so prevalent in current American cinema.

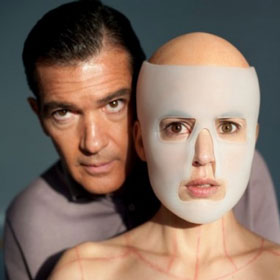

I wonder what it means for The Skin I Live In to be the first Almodovar film someone sees. When I saw Talk to Her nearly a decade ago I was floored, and made plans to show it to everyone I knew. The Skin I Live In, despite starring an aged but still dashing Antonio Banderas, perhaps makes for a difficult introduction to a brilliant filmmaker's astounding oeuvre, similar to the way tackling Finnegan's Wake is hardly the best means to ease oneself into modernist novels. But I hope, for the sake of joy in encountering strange things that mean nobody harm, audiences will un-pretzel themselves out of whatever naturalism The Skin I Live In offends and find some repose to enjoy it. That's the key to this amazing work of art.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment