'Life Itself' Review: Documentary Shows Roger Ebert As An Intelligent, Cinema-Loving Journalist

4/5

After 46 years of “thumbs-up” or “-down” to every crumb, slab or sliver of cinematic art, it seems only fitting that late Chicago film critic Roger Ebert is the subject of a feature-length documentary, Life Itself, directed by Steve James (Hoop Dreams). It is sad, too, given that filming began after Ebert’s jaw was surgically removed due to cancer, taking with it his ability to speak, and ended around the time of his death, in April 2013. Those who remember Ebert as the bespectacled, rotund and vociferous half of Siskel & Ebert, who appeared on television from 1975 to 1999, will need time to adjust to the fact that only the spectacles remain.

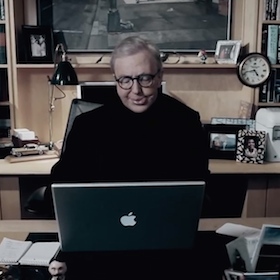

Life Itself is loosely based on Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same name — loosely because only certain chapters are used to provide biographical backing, and the film picks up where the book leaves off. Except for a brief interlude at Ebert’s home, James’ new footage is acquired mostly at the hospital, where Ebert eats through a feeding tube and types his wisecracks into a voice-generating MacBook. Mostly bed-ridden, he is occasionally shown attempting physical therapy on a Stairmaster. The cartilage of his lower lip and jaw, crudely reconstructed, dangles and quivers, making any viewer uneasy. The word “unflinching” — used probably a thousand times in Ebert’s reviews of films he deemed unapologetic — comes to mind, but I’m squeamish about it now. It’s as if documentarians like James can’t flinch when their eyes are attached to a camera — they zoom in, showing us more than we asked to see.

Let that be a warning to those in search of a purely heartwarming tribute to the life and work of America’s most popular movie critic. Sure, you witness the humble beginnings (he grew up in small-town Illinois and attended a public college), the groundbreaking accolades (a Pulitzer, for criticism, in 1975), and the triumphs over everyday struggles (alcoholism, depression, bachelorhood), but you also watch Ebert suffer through a medical procedure that clears his airways. Filming for that scene takes place unbeknownst to Chaz, Ebert’s wife, who thought it too vulnerable. (She was right.)

Life Itself tells, effectively, two love stories, neither of them conventional. Ebert’s marriage to Chaz when the film critic was 50 is the more obvious. The more interesting is that between young Ebert and the reviewer for a rival Chicago newspaper, Gene Siskel. When the two men first started filming what was then called Sneak Previews, in 1975, they were like plaids and stripes — Siskel, the Yale-educated playboy with a philosophy degree, and Ebert, the Midwestern news junkie with a Pulitzer Prize. They clashed, both on-camera and off, and only warmed up to each other slowly. Some of the funniest moments in Life Itself emerge from outtakes of the two critics filming promos for their syndicated show, in which they attack each other’s tastes, reputations and speech patterns. Theirs was a hostile friendship, but a long-lasting one, ended only by Siskel’s death, from a brain tumor, in 1999.

Ebert’s spats were not limited to those he shared with Siskel. As his popularity grew, many film critics grew annoyed with the yes-or-no, heads-or-tails rating system that Ebert’s TV show popularized. They weren’t just sick of seeing movie posters displaying the ubiquitous phrase, “Siskel and Ebert give it two thumbs up!” They thought serious film criticism, practiced by the likes of the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, was in jeopardy, and Ebert’s overly simplified judgments weren’t helping.

One such critic was Time magazine’s Richard Corliss, who sounded off against Ebert’s two-thumbs rating system in the pages of Film Comment. His tone is condemning:

"Will anyone read this story? (It has too many words and not enough pictures.) Does anyone read this magazine? (Every article in it wants to be a meal, not a McNugget.) Is anyone reading film criticism? (It lacks the punch, the clips, the thumbs.) Can anyone still read? (These days, it's more fun and less work just to watch.)"

Ebert’s willingness to argue, however, was unwavering. His rebuttal to Corliss, printed in a subsequent issue of the same journal, takes the Time critic to task for inaccuracies and hypocrisies, and Ebert reveals an intelligence so sharp it’s a wonder he’s also as famous as he is. Other film critics on TV at the time, as he points out, didn’t have his background in print journalism, and they didn’t know as much about both the history and current state of filmmaking as he did.

Before I saw Life Itself, I thought of Ebert as someone like the John Steinbeck of film reviewing — solid and popular, but not truly great. Not Hemingway, certainly not Fitzgerald. His reviews I’d read were clear but seemed facile, as if he’d formed his opinion and written half the review before the credits rolled. (According to the documentary, this was often the case.) While I stand by my initial judgment of Ebert’s later writing, I find that he seems simply to have relaxed his prose style while keeping his mind sharp and his passion for good filmmaking, and good writing, strong. This legacy strikes me now a better one to leave behind — not as an inventor on the page but as an intelligent, effectual, appealing writer in real life, whose enormous body of work says it all.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment