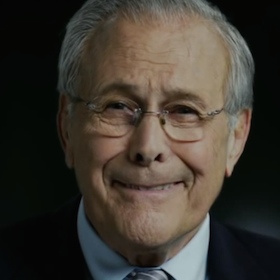

'The Unknown Known' DVD Review: Donald Rumsfeld Remains A Mystery

4/5

Donald Rumsfeld was known for his theater of cleverly disguised responses and his army of memos. The Unknown Known is Errol Morris’ follow-up to his Academy Award winning documentary/interview/interrogation Fog of War. Instead of Robert McNamara as its subject, this time it’s another polarizing and inscrutable figure in American politics: former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The title derives from Rumsfeld’s own records. According to him they are:

1) Known knowns: the things we know we know.

2) Known unknowns: the things we know we don’t know.

3) Unknown known: the things we don’t know we know.

4) Unknown unknowns: things we don’t know we don’t know.

Confused? Don’t worry, apparently Rumsfeld messed this up in some of his memos as well. However, these four little notes are the driving force of the interview.

The first question Morris asks Rumsfeld is how he would examine himself. What words would he use? “Measured. Cool,” Rumsfeld replies. That’s part of the problem with this entry: Rumsfeld remains measured and cool. For those interested in seeing a Frost/Nixon moment, this can be both frustrating and somewhat unsettling. A perfect example of this comes when proper evidence is cited that, had things worked out only slightly different, it would have been Donald Rumsfeld running for president after Ronald Reagan. Rumsfeld said yes, he could have been President, in a matter-of-fact, no big deal kind of way that makes you wonder if you’d heard the question wrong, that Morris had actually asked if his favorite color was blue.

The history is too new to see how Rumsfeld’s legacy will be remembered. His mark is an indelible one, however, and that will keep us talking about him long after he’s gone. The problem is we still won’t know what to make of the man. Morris does have an agenda, of course, to continue to paint the former SecDef as a villain, and even as Rumsfeld takes the bait, we see that this is somewhat fun for him; Rumsfeld has a flair for language and rhetoric.

They engage in an etymological and philosophical duel more than anything else. Rumsfeld is precise in his wording, using simple terms to truly say nothing at all; Morris is prodding and confrontational, but also patient. It’s by the halfway mark that Morris seems to realize that the only thing he can do is keep Rumsfeld talking and use his words to fashion a noose. Even then there are no real exclamation points, though they both land a few gotcha moments.

In some ways this is more akin to My Dinner with Andre than it is an interview. There is a strange familiarity at play here between these two; Morris has written quite a bit about Rumsfeld, and his articles are available as bonus material on the DVD. There’s also material from the interview that didn’t make it to the final version — Rumsfeld didn’t care for either cut, truth be told — and a subdued commentary track that is Morris essentially watching the documentary and once in a while speaking a few words. It’s here, in this largely silent commentary, when he does actually speak, that Morris’ agenda becomes clear; he wants everyone to see Rumsfeld as a reptile, and in many ways he is. But the fact that Morris went into this with a specific motive is in poor taste and only obfuscates the matter further.

The thing is, this release isn’t about the bonus footage. It’s not like Blade Runner where you’re buying a well-known story for the trivia and insight you didn’t already have; the main event is the sparring between Morris and Rumsfeld.

The Unknown Known has been unfairly compared to Fog of War. Despite the fact both were from Errol Morris, they’re two entirely different beasts simply because of their subjects. While both Rumsfeld and McNamara were Republican SecDefs, mysterious, strange (which was McNamara’s actual middle name!) and controversial, they both took the opportunity of the interview differently. McNamara took a particularly Roman Catholic approach and treated it as a confession. For all of his coldness, there was a man who had accurately measured his own life, and with a surprising amount of self-awareness, told us what he got wrong and what he got right. Rumsfeld however, through his grandfatherly grins, uses this more as a game to flex is rhetorical muscles that might’ve begun to atrophy in his years outside the public light. Rumsfeld does break down for a moment, the way McNamara did, in speaking about the soldier he encountered at Walter Reed, and even asks the question of if it was all worth it. However, he doesn’t go on to answer his own question. While McNamara’s break down was cathartic, this one fell short, like Rumsfeld suddenly remembered he was on camera.

The most effective moments in the documentary come from Morris having Rumsfeld read some of his memos that span his entire career; the memos were saved within the Pentagon. He had written so many over the course of his career that both he and his staff called them snowflakes; Rumsfeld postulates that there are likely “millions” out there. They represent, sometimes, a good view of who he is; sometimes — specifically his Middle Eastern review from the 1980s — they represent crushing historical irony, and sometimes they’re just sad.

Even within his own party, Rumsfeld remains a mystery. Richard Nixon and Bob Haldeman considered him a political climber with no real loyalties; George H.W. Bush didn’t like him; Reagan tolerated him; Dick Cheney was his friend. Blame gets thrown around, excuses get made, responsibility is sometimes taken, but the greater mosaic of the man remains as obscured as a figure in a blizzard. For the rest of us, the only thing we know we know about Donald Rumsfeld for certain is that we don’t really know him.

RELATED ARTICLES

Get the most-revealing celebrity conversations with the uInterview podcast!

Leave a comment